China’s New Climate Disclosure and What It Means for Us

China’s New Climate Disclosure and What It Means for Us

If you want to know where the economy is headed, watch the footprints of the elephants. In climate political economy, “the elephants” are policy moves in the US, China, and Europe.

They don’t just set domestic rules. They shape what becomes “normal” for global capital, trade, and supply chains.

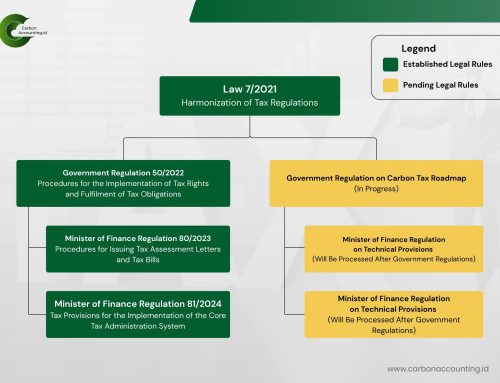

At the end of December 2025, China released the Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Standards for Business Enterprises No. 1: Climate (Trial), often called CSDS-1. It’s a major step to align climate disclosure with the IFRS S2 direction, creating a common language for how companies explain climate risk, climate strategy, and climate performance.

Structurally, it will feel familiar to anyone who follows TCFD and ISSB: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics & targets. It covers physical and transition risks, climate opportunities, scenario analysis, and the Scope 1-2-3 emissions architecture. It also expects disclosure of climate targets, both internally set and regulator-mandated, as well as reports on progress.

But CSDS-1 is not a copy-paste of IFRS S2. China is building something that also serves public policy and regulatory needs, not only investor decision-making. It signals a gradual ramp: from voluntary to mandatory, and from qualitative storytelling to more quantitative accountability.

CSDS-1 also has distinctive disclosure hooks. It introduces explicit “climate-related impacts” requirements (not only climate risks), and asks that impact information stay consistent with other legally required environmental disclosures when both are published. It also pushes transparency on the financial effects of climate-linked instruments-carbon emissions rights trading, green energy certificates, voluntary reductions, renewable energy contracts, items that increasingly show up in financial statements.

So, what does this mean for businesses in Indonesia? The impact won’t stay inside China. It will travel through supply chains, financing, and investment. As Chinese companies and financial institutions adopt this discipline, they will naturally ask suppliers, project partners, and investment targets for cleaner climate data, because they need it to report, to price risk, and to defend decisions.

In practice, Indonesian firms (especially those tied to China facing sectors) should expect more frequent requests for emissions data, transition evidence, and auditable proof in procurement, due diligence, bank financing, and investor conversations. Because when the elephant is already moving, you either move with it or stand still and get trampled.