Why IPSASB SRS-1 Could Change Indonesia’s Climate Governance

Why IPSASB SRS-1 Could Change Indonesia’s Climate Governance

At the end of 2024, a friend from Indonesia’s Audit Board (BPK RI) handed me an IPSASB exposure draft and asked, “You’re in sustainability, what do you think?”

I read it slowly, expecting another ESG-style document. But the deeper I went, the more it felt like something else: a blueprint for turning climate issues into the kind of accountable, auditable information we usually reserve for financial reporting.

When I finished, my response was brief, “If implemented, this would be revolutionary”.

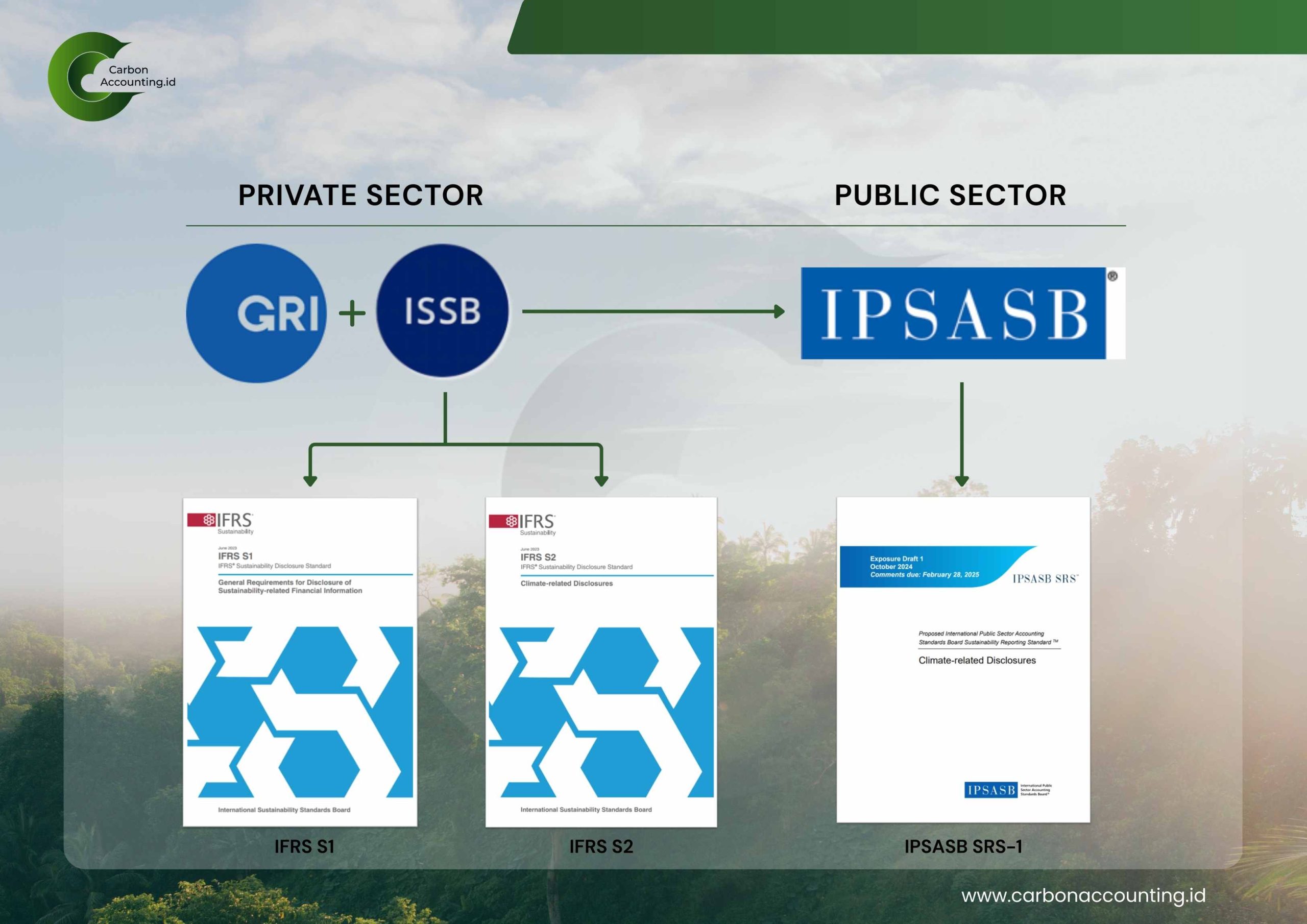

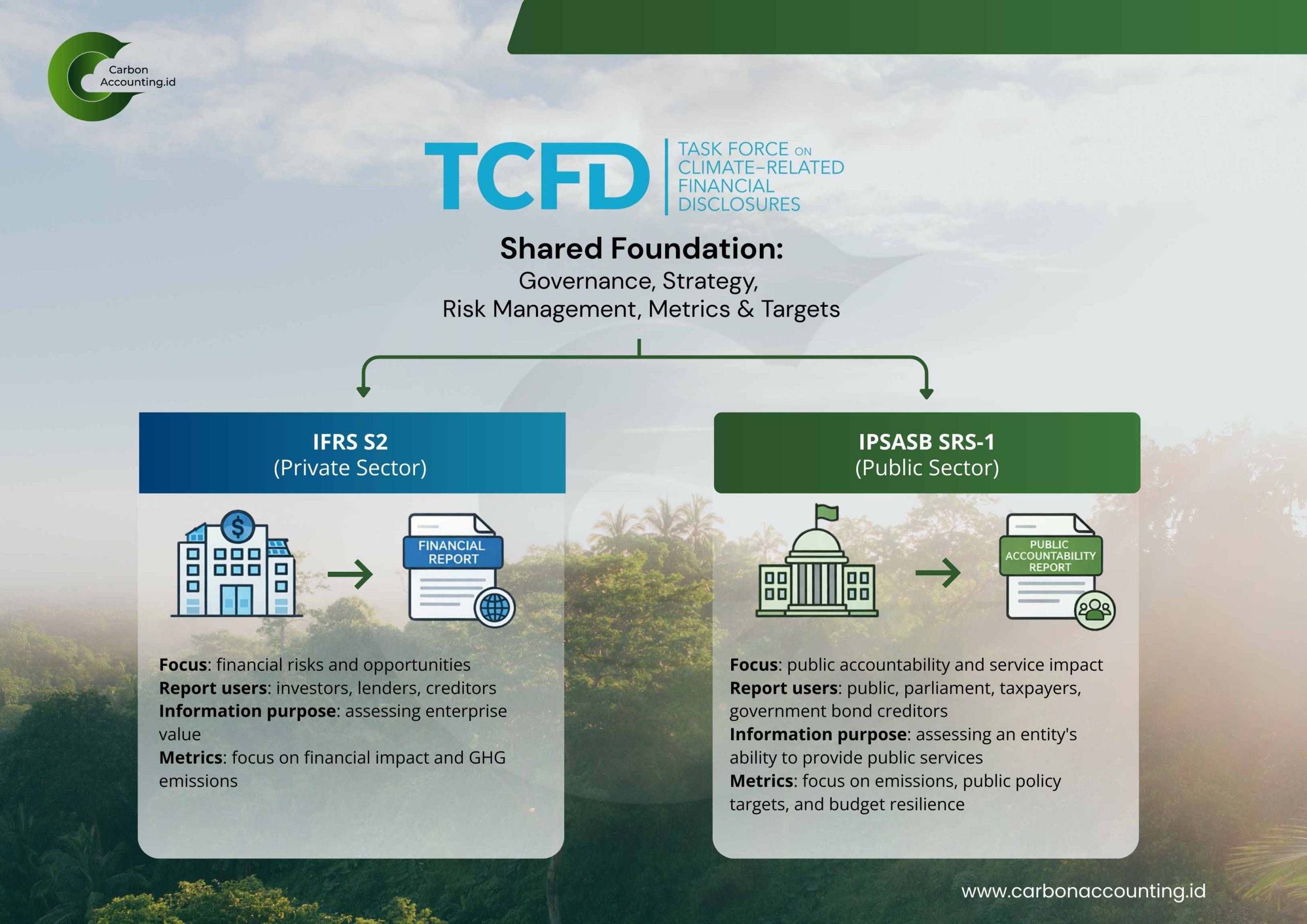

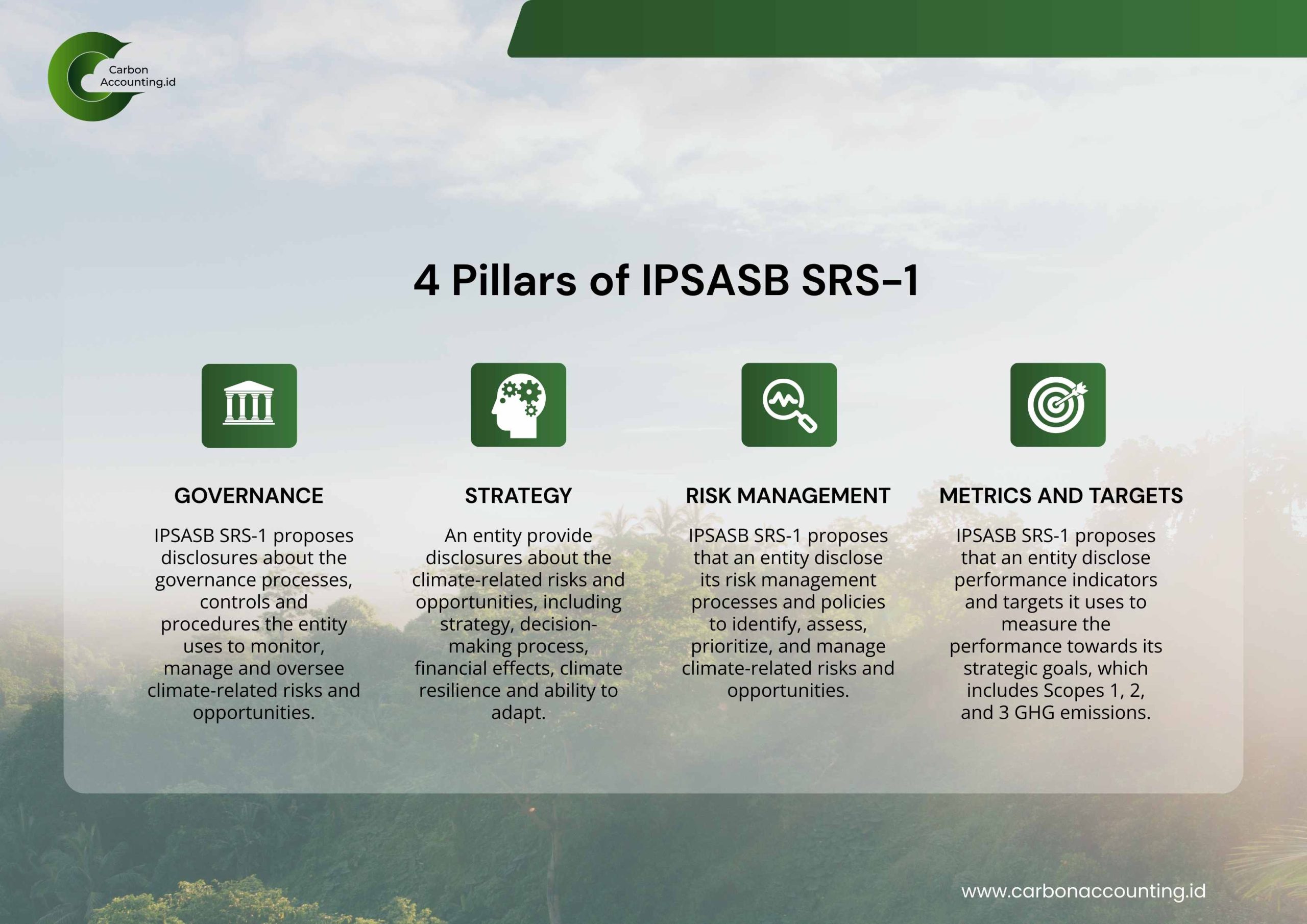

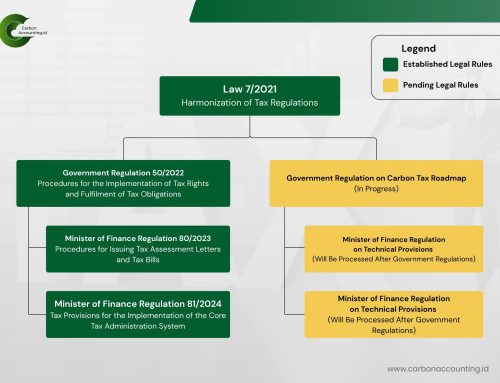

That intuition became more concrete in December 2025, when the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) ratified its first Sustainability Reporting Standard (SRS-1), effective January 1, 2028 (early adoption permitted). On the surface, SRS-1 looks like IFRS S2 (PSPK 2). It follows the familiar TCFD/ISSB logic of Governance, Strategy, Risk Management, Metrics & Targets. It aligns emissions disclosure with the Scope 1–2–3 concept used widely in practice.

The key difference is where it applies: not corporations, but governments and public sector entities, from central and local governments to ministries, agencies, commissions, authorities, and international public organizations.

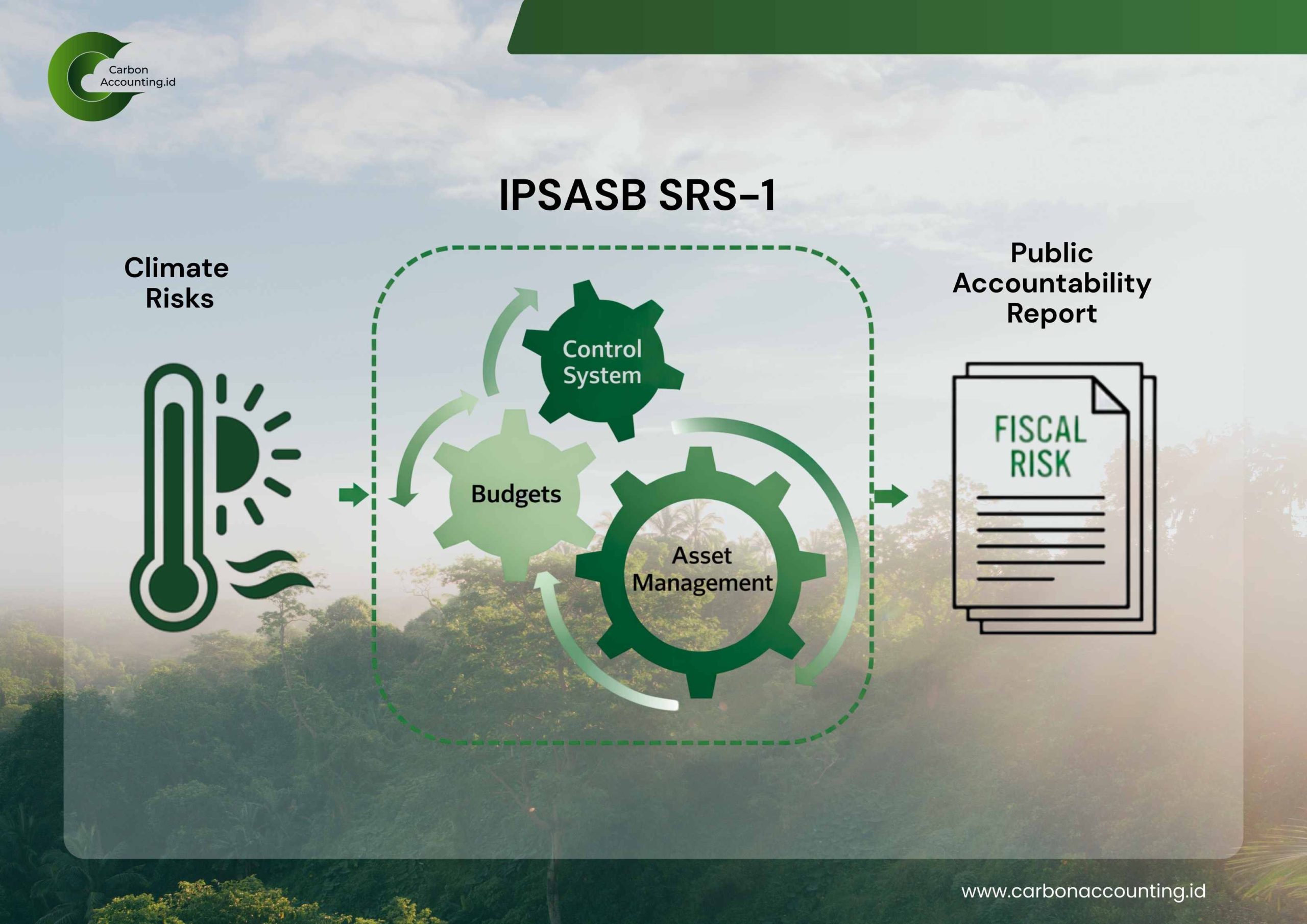

Why does this matter for Indonesia? Because SRS-1 quietly pulls climate governance out of “policy documents” and into the machinery that actually runs the state: procurement, asset management, and the APBN/APBD cycle.

Once climate-related information becomes mandatory for public entities, a practical question follows immediately: where does the data come from? The answer often lies in suppliers and contractors. Over time, this pressure can change procurement behaviour, vendors may be asked for credible carbon footprint data, not as marketing, but as governance evidence.

The standard also reframes public assets and services as climate-sensitive systems. Buildings, hospitals, schools, and transport networks are not neutral in a warming world. They face physical risks, operating cost pressures, and service continuity challenges. If climate risk is treated as reportable, it also becomes harder to ignore fiscally: climate risk starts to look like fiscal risk, affecting long-term resilience and the affordability of public services.

The real shift is not the template. It is the discipline. SRS-1 nudges climate governance toward the habits of financial governance: clearer roles, documented processes, traceable data, internal controls, and “connected” narratives across reports. If Indonesia leans into this early, SRS-1 can be more than compliance. It can be a governance upgrade, making procurement more future-proof, public assets more resilient, and budgets more intelligent about long-term climate risk.