Over the Coal Shadow, Before Hydrogen: Timing Indonesia’s Gas in the Transition

Over the Coal Shadow, Before Hydrogen: Timing Indonesia’s Gas in the Transition

Indonesia’s energy conversation has a new protagonist: natural gas. In recent years, the government and operators have spotlighted sizeable finds: Kali Berau Dalam in South Sumatra (~2 TCF), Timpan-1, Tangkulo-1, and Layaran-1 offshore Aceh (~1.5, ~2, and ~6 TCF respectively), and Geng North-1 in East Kalimantan (~5 TCF). With aggregate resources that are anything but trivial and lifecycle emissions far lower than coal, the entrenched backbone of the power mix, the question writes itself: can gas meaningfully accelerate Indonesia’s energy transition on the road to Net-Zero Emissions (NZE) 2060?

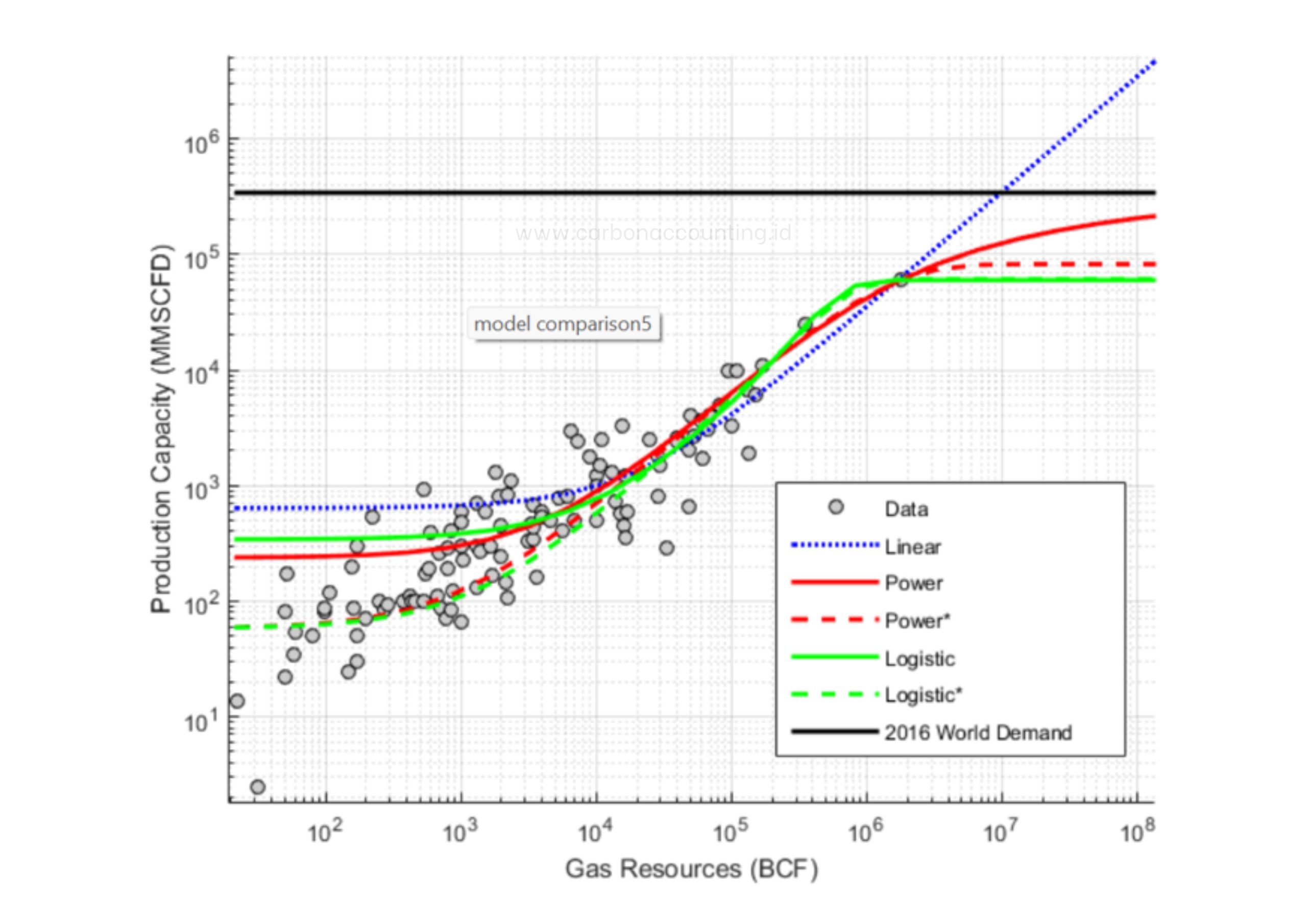

From CarbonAccounting.ID’s perspective, the answer is “potentially yes, if we move fast and deliberately.” Our open working paper on SSRN, “Horizontal Asymptote in Natural Gas Production Capacity”, indicates that reserves above ~0.2 TCF tend to clear the threshold for economic viability under reasonable development scenarios. Indonesia now has multiple prospects well above that bar. Technically, that places gas in a strong position to serve as a transition fuel through the 2030–2060 window, complementing renewables by providing dispatchable capacity and anchoring industrial heat where electrification lags.

Yet abundance on paper does not automatically translate into climate-aligned value. Gas sits within a narrowing “window of opportunity.” Two opposing forces squeeze this window from different ends of the timeline: near-term price competition with coal, and longer-term disruption from zero-carbon molecules. Navigating that squeeze requires both speed and strategic sequencing, commercial decisions must align with climate targets and evolving cost curves.

In the short term (2025–2040), coal’s incumbency is formidable. With existing mine-mouth plants, sunk infrastructure, and currently modest carbon offset prices, coal retains a unit-cost advantage in many dispatch stacks. Gas projects must therefore overcome not only capex and midstream bottlenecks but also a pricing regime that has historically favored baseload coal. Without targeted reforms, contracting frameworks that reward flexibility, grid rules that value ramping, and transparent carbon pricing, even efficient gas may struggle to displace coal at scale.

In the long term (2040–2060), the headwinds change character. As carbon offset costs rise and technology learning curves steepen, green hydrogen emerges as a credible substitute for gas in power, industry, and transport. Unlike gas, green hydrogen carries no scope-combustion emissions, eliminating future exposure to high carbon costs. If hydrogen production, storage, and end-use technologies achieve expected cost declines, late-cycle investments in new gas capacity risk stranding or require expensive abatement to remain competitive.

That is why timing is everything. Indonesia’s gas can be a productive bridge only if development is accelerated and disciplined. The policy objective should be to monetize viable fields early, target applications that deliver the biggest emissions cuts per rupiah (coal-to-gas switching in flexible generation and hard-to-electrify industrial heat), and lock in designs that are compatible with a high-carbon-price future. Do that, and gas helps smooth the climb to NZE 2060; miss the window, and today’s discoveries could become tomorrow’s stranded potential. From our seat at CarbonAccounting.ID, the playbook is clear: move quickly, prioritize climate-efficient use cases, and plan every gas decision with the endgame (zero-carbon competitiveness) already in view.