The Price of Indonesia’s Delayed Energy Transition

The Price of Indonesia’s Delayed Energy Transition

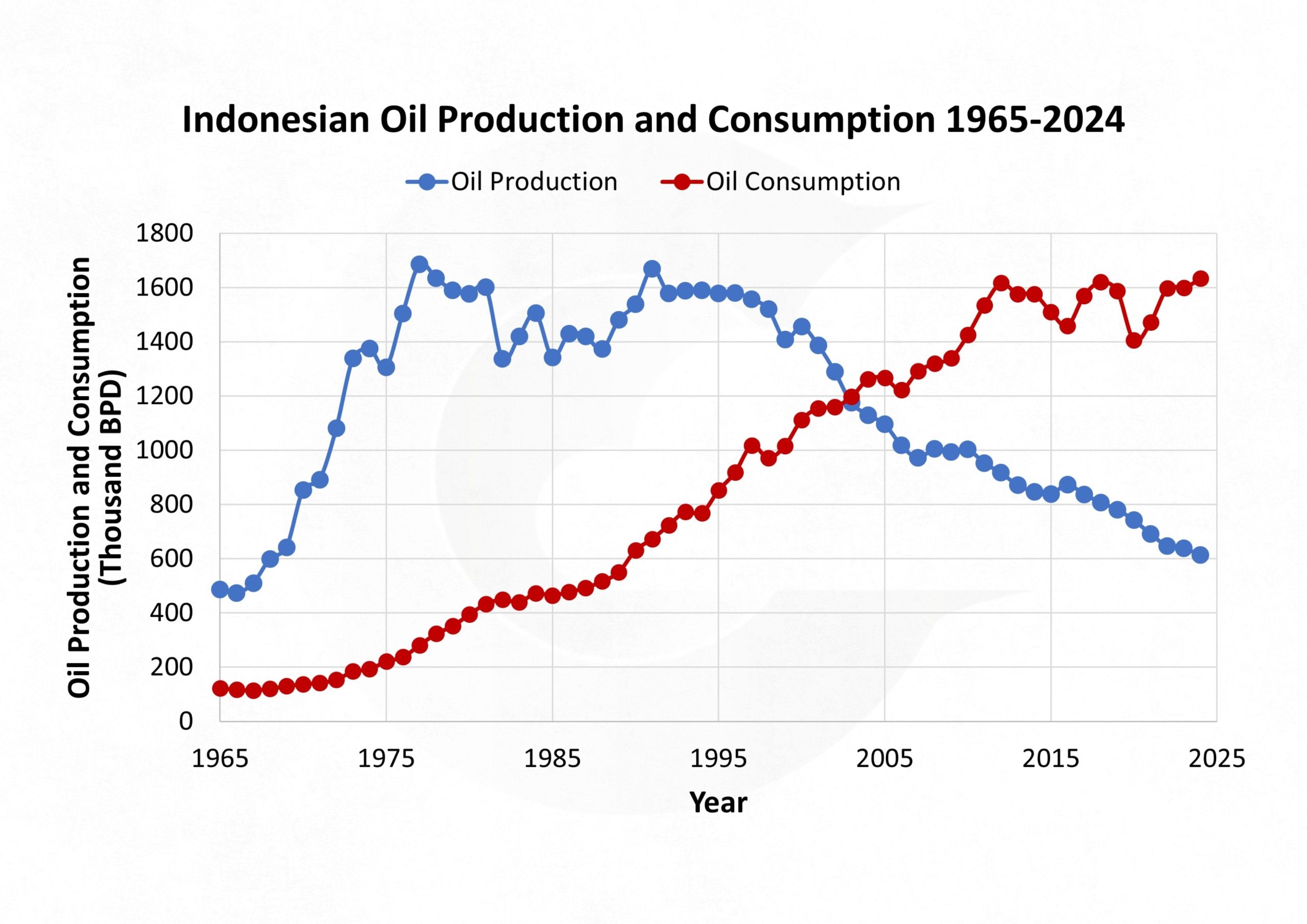

Two trends have been moving in opposite directions for years. On one side, Indonesia’s crude oil production has declined to roughly 570-580 thousand barrels per day in 2024-2025, despite repeated efforts to arrest the fall. On the other, domestic fuel demand has continued to rise, driven by transport, industry, and petrochemicals. The gap between what we produce and what we consume is now filled by imports, about one million barrels per day of crude and refined products according to government statements and international data.

Our 2017 depletion model suggests that this production decline is not a blip but a structural trajectory. Pushed forward to 2050, the Asymmetric Logistic curve points toward output in the 200-thousand-barrel-per-day range if no extraordinary new discoveries materialize. Meanwhile, policy still leans heavily on refinery expansion and fossil-based infrastructure rather than an aggressive pivot to electrification and renewables. The risk is clear: we lock in capacity to process oil we no longer produce, but still need to import at scale.

The import bill is already large. With net imports around one million barrels per day and oil prices in the USD 75-80 per barrel band under mainstream scenarios, Indonesia is effectively writing cheques of roughly USD 29 billion a year for oil, around 2% of current GDP.

Under the International Energy Agency’s current-policies scenario, crude prices could exceed USD 100 per barrel by 2050, which would push the oil import bill above USD 51 billion per year if consumption remains the same.

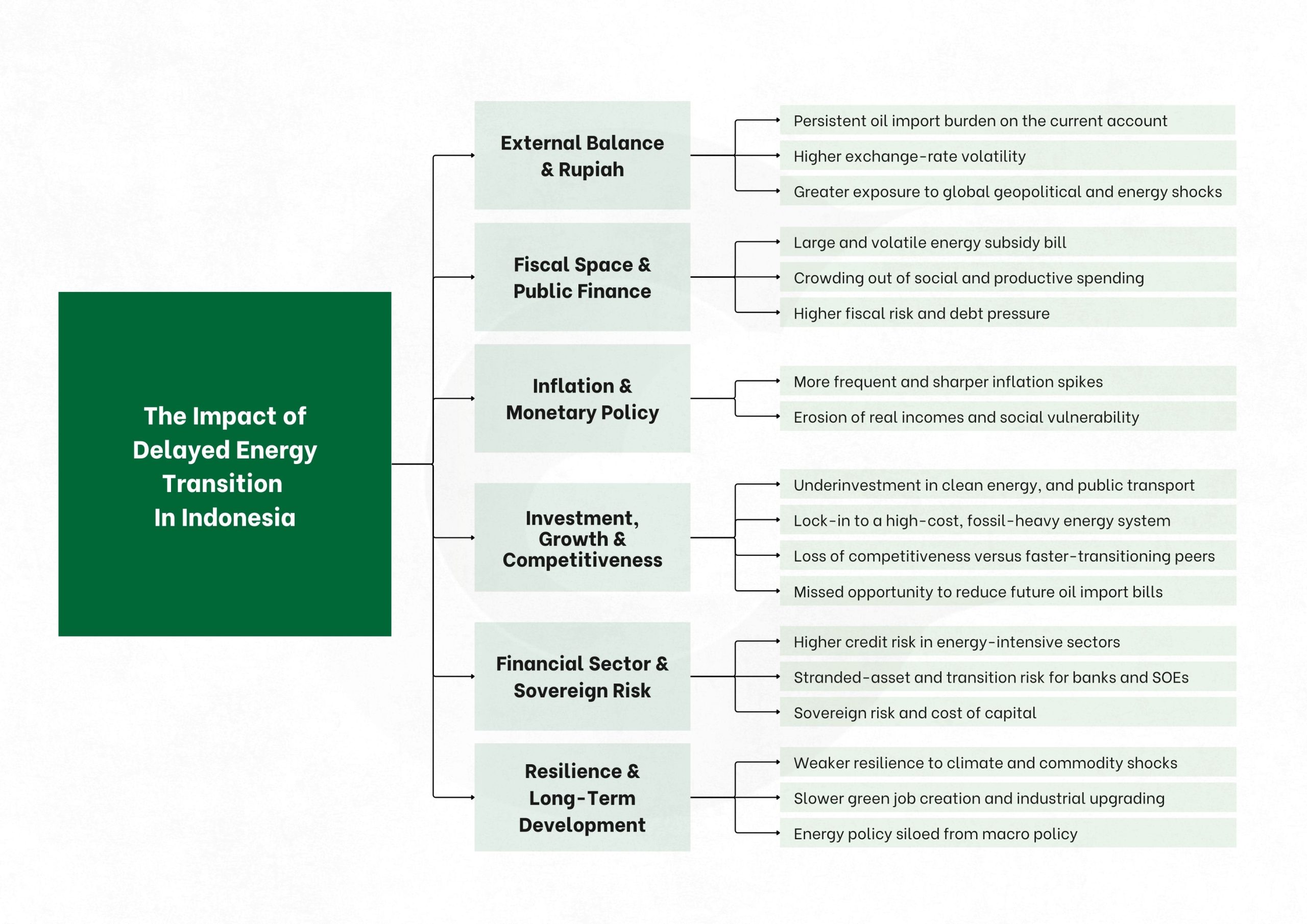

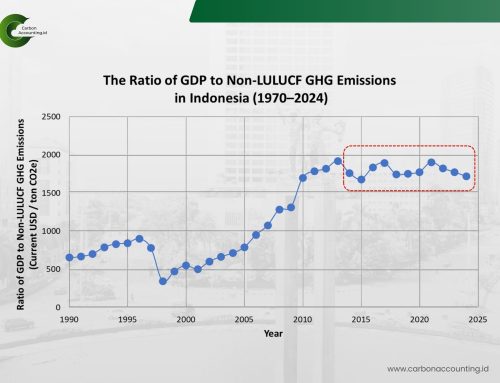

The macroeconomic implications are not abstract. A persistent oil import bill of that magnitude weighs on the current account, pressures the rupiah, and constrains fiscal space, especially when combined with fuel and electricity subsidies used to cushion domestic prices. Recent episodes of currency volatility and targeted energy subsidies illustrate how quickly external shocks translate into domestic policy trade-offs. Every dollar spent on imported fuel is a dollar not invested in transmission lines, renewable capacity, public transport, or climate adaptation.

From CarbonAccounting.id’s perspective, this is the true price of a delayed energy transition. Oil depletion curves and import statistics together draw a simple picture: relying on ever-more expensive imported oil is not a development strategy. It is a vulnerability.

The alternative is to treat depletion forecasts as a planning baseline, accelerating efficiency, electrification, and renewables so that by the time production is closer to 200 thousand barrels per day, Indonesia’s economy is no longer hostage to the global oil market. Our work on modelling, GHG accounting, and climate-risk analysis is aimed at helping institutions quantify this risk and act before the bill becomes unmanageable.